- Home

- Janice Harrington

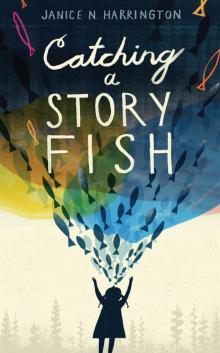

Catching a Storyfish Page 2

Catching a Storyfish Read online

Page 2

Well, isn’t that something.

I was just thinking about doing a little fishing.

Would you like to go?

Keet:

Yes, Grandpa.

YOU’RE A WIGGLE WORM

“Can I go, Keet-y?”

“No. Just me and Grandpa.”

“Why can’t I go?” Nose says.

“You’re too small,” I say.

“A catfish might eat you.”

“Can’t I go to Grandpa’s house?”

“No, not this time.”

“Why can’t I go?”

“You wiggle too much.

Grandpa might think you’re a worm.

He’ll put you in his tackle box

and use you for bait,

and then a catfish will eat you for sure.”

“I don’t want a catfish to eat me.

Keet-y, tell Grandpa I’m not a worm.”

“Grandpa can’t help it.

He likes catfish.

And you’d make a good worm.

A really, really big catfish

will eat all your toes,

and tickle you

with its catfish whiskers, like this.”

“No! Keet-y, noooooo!

I’m not a worm!”

“Yes,” I say. And I chase him

all over the house.

“Catfish tickles!

Catfish tickles!

Wiggly Nose

gets catfish tickles!”

GRAB THE TACKLE BOX!

Now that we moved

I go fishing with Grandpa

not just on summer visits,

not just on his trips back home,

but every Saturday.

“We’ll go rain or shine

or sweet potato,” Grandpa says.

He picks me up in his truck, Big Blue,

and we ride bumping up and down the road

looking for the best fishing holes.

I’m Grandpa’s fishing buddy.

He calls me “Fish Bait.” But

when I talk too much and

scare the fish, he calls me

“some 70 pounds of trouble.”

On Fishing Days, we grab

Grandpa’s tackle box.

It has fishing line, sinkers, bobbins, pliers, and bait.

We grab our fishing hats and mud boots.

We grab fishing poles, buckets, lunch sacks,

peanutbutterdillpickle sandwiches,

and mud juice (that’s what we call chocolate milk),

and lots and lots and lots of marshmallows.

Sometimes, Grandpa builds a fire.

We melt marshmallows and eat them

ooey-gooey on the end of a stick.

Sometimes, we nibble them—fat, soft,

and sugar-dusty—from the tip of a straw.

I call them marshmallow mops.

Grandpa says, “Mm-mm-mm,

my belly had one empty spot left

but I think that put a plug in it.”

JUST THE RIGHT SPOT

We stomp through fields and weeds.

We swing our buckets back and forth.

We step-step-high and step-step-low

while Grandpa looks for a good spot to fish.

“Catfish like places to hide,” Grandpa says.

“They like still and slow and muddy.”

Grandpa knows my tongue

is wiggly as a wiggle worm

and quick as a mosquito,

so wherever we look, he says, “Shhhhhh.

Shhhhh. The fish will hear you.”

“Really, Grandpa?”

“Yes,” he whispers.

“They’ll hear your heart beating through the fishing line,

hear your heels hard-thumping on the bank,

hear your bottom bouncing and wriggling all around.

“Shhhhhh, Fish Bait,

shhhhhh.”

FISH BAIT

Grandpa baits his fishing hook,

and then he tries to bait mine.

He plucks a worm out of a coffee tin.

“No, Grandpa, too tickly.”

He pushes a dough ball

from a plastic sack.

“No, Grandpa, too stinky.”

He pulls a froggy-kind-of-thingy

from his tackle box.

“No, Grandpa, too rubbery-slippery.”

“Well, Fish Bait,

how do you plan to catch a fish?”

I rub my nose and think a bit.

Then I look in my lunch sack.

“Marshmallow, Grandpa!

I’ll bait my hook with a marshmallow.”

FISHING LESSON #1

“You need to think like a fish,” Grandpa says,

“if you’re going to hook a fish.

“And the only way to think like a catfish

is to listen. Catfish are great listeners.”

“Catfish don’t have ears, Grandpa.”

“Yes, they do, Fish Bait.

Yes, they do.

“Sound slips through their bodies

like water and tickles their bladder,

and tickles their bones,

and tickles their inside ears,” Grandpa says.

“If those catfish hear a wiggly-giggly girl,

a wiggly-giggly, can’t-sit-still,

word-buzzy girl, they’ll hide

double-quick and sink down in the mud.

“To catch a fish,” Grandpa says,

“you’ve got to sit quiet and hold still.

You’ve got to listen, really listen

with your inside ears.”

“Inside ears, Grandpa?”

“That’s right, Fish Bait. Deep inside

where no one else can see ’em.”

“Is that true, Grandpa?”

But all he says is,

“Shhhhhhhhhhhhhh.”

FISHING LESSON #2

Shhhhhhh. The leaves rub,

the leaves rustle.

Grandpa’s breath

scrapes in and out.

Water slicks and licks the bank.

Frogs drum ah-RUM-ah-RUM,

dragonflies zummmm,

mosquitoes zeeee,

blue-bottomed flies go zzu,

and zzu, and zzzzzu.

Splish!

Plop!

Splash!

I’m a catfish girl floating above deep, cool mud,

catfish quiet, catfish still.

I’m a catfish listening with my whole body.

BEDTIME STORIES

“Listen,” Nose says.

“Listen, Keet-y, listen to me tell it:

Oogle-oogle-oogle go away!”

Nose screws his face tight.

He looks monster-mean.

He shows his claws.

He says, “I’m going to chomp

and chomp and chew you up!

Tell me the story, Keet-y.”

“Not now, Nose.”

“Pleeeeease!” Nose says.

“If I tell you, will you go to bed?”

“Yes,” Nose says.

“Promise?”

“Yes,” Nose says.

“Tell me the story,

and make me chocolate milk,

and read to me, and then

tell me another story,

and then I’ll go to sleep.”

Little brothers make a lot of trouble.

KEET’S STORY FOR NOAH

Once upon a time, there was a little boy

who really, really liked chocolate milk.

One night, he went into the kitchen

to get chocolate milk in his favorite cup

covered with great big blue dinosaurs.

He had just poured a super-gigantic cup

of chocolate milk

when he heard something right behind him.

“The Oogle Monster!” Nose says.

“Yes,” I say, “the Oogle Monster.”

said in his oogle-oogle voice:

“I’m going to chomp and stomp

and chew you up!”

“Chew you up,” Nose says. “Chew you up!”

The little boy did not want to be eaten.

He wanted to drink his chocolate milk

in his super-gigantic cup with blue dinosaurs.

So he said in a loud voice,

“Oogle-oogle-oogle, go away!”

The Oogle Monster

had never heard such a loud voice.

It made him tremble.

It made him shake.

He covered his ears—

and then he stuck his head through the kitchen floor.

The little boy started to tiptoe,

tiptoe, tiptoe back toward his bed.

But once more he heard something

right behind him.

It was the Oogle Monster,

and the Oogle Monster

said, “I’m going to chomp and stomp

and chew you up!”

The little boy didn’t want to be eaten.

He wanted to drink his chocolate milk.

So he said in a soft, soft voice,

“Oogle-oogle-oogle, go away!”

The Oogle Monster

had never heard such a soft, sweet voice.

It made him yawn.

It made him fall fast asleep

right on top of the kitchen floor.

“And he snored really loud,” Nose says.

“Yes, he did.”

“And the little boy’s mother came,”

Nose says.

“Yes, she did.”

The mother said, “Oogle-oogle-oogle, go away!”

And she swept the Oogle Monster up,

and washed him down the sink.

Nose laughs and laughs.

“She washed the monster down the sink!”

he says.

I pour icy-cold chocolate milk

into his big blue dinosaur cup.

And Nose drinks it up, up, up—

and burps!

FISHING LESSON #3

In bed at night, I listen.

I pretend

I’m a night catfish.

I pretend

the stars are catfish looking down

and listening.

I hear my baby brother

singing Oogle-oogle.

I hear Mama and Daddy

talking low.

I hear the moths flutter-beat

against the window.

I hear the door of my room quietly open

and feel Mama’s breath against my cheek

and Daddy tuck-tucking my blanket.

“Sweet dreams,” Mama says.

“Night-night, Keet,” Daddy says.

I try to listen with my inside ear,

and I hear the worry in Mama’s voice.

She wants me to be happy here.

I listen with my inside ear,

and I hear long roads in Daddy’s voice.

He’s working hard for us. He’s working hard for me.

Their voices swim inside of me

like silvery fish, until I fall asleep.

NEW SCHOOL

Down in my stomach

I feel grasshoppers, tadpoles,

and the silvery minnows that dart

and swim beside the bank.

Down in my stomach

I feel wiggly worms and eels.

Monday, I’m going to a new school.

Mama says it’s a small school, a good school.

But I’ll be the new kid.

Down in my stomach

I feel bubbling and sinking.

In a few days, I’ll learn new names

and new faces, go to new classes

with new teachers, new

rooms, and new desks.

And I’ll be the new kid.

Down in my stomach

I feel a question

like a pointy fishhook:

What if I don’t like it?

Chapter 2

FIRST WEEK: WHY DO YOU TALK THAT WAY?

BELLS

Feet pounding,

laughter rising,

words flying,

kids flocking.

Bells.

Pencils dropping,

buses stopping,

moms pecking kiss, kiss,

dads squeezing hug, hug,

big kids,

little kids.

Bells.

Principal pacing

back

and forth,

teachers talking,

fast walking,

doors opening,

doors closing.

Bells.

Desks screeching,

chairs scraping,

PA squawking,

janitor mopping.

Bells.

Kids in lines,

kids in bunches,

quiet kids, loud kids,

kids chasing,

kids running,

kids yelling,

Bells.

WHAT ALLEGRA THOUGHT

Nobody’s quiet. Everyone’s talking,

everyone except

the New Girl.

The kids look at her

the way they looked at me

when I was new.

I wonder what she’s like.

I wonder what she likes to do.

I draw her five pigtails.

I draw her socks—blue with pink hearts.

I draw her great big eyes,

New-Kid Eyes that look at everything

and seem s-c-a-r-e-d.

FISHHOOK EYES

Their eyes look like pencil points.

Their eyes go scribble, scribble

and poke, poke.

Their eyes are fishhooks.

“Class, this is Katharen Walker.

Katharen, can you tell us

where you went to school before?”

“Vernon Elementary School,” I say.

A boy in the front row laughs.

A girl says, “You sound funny.”

“And where is that, Katharen?”

I didn’t know

that words could have hard edges.

I didn’t know that words

could get stuck in your throat.

“In . . . Alabamer,” I say.

But I don’t say it very loud,

and the teacher asks me to repeat it.

“Alabamer.”

“Alabama? Very good. Welcome

to your new school, Katharen.

I have friends from the South,

and I’ll look forward to learning

more about you.”

“Yes, Ma’am,” I whisper,

but already I can tell that I made

another mistake.

Nobody says that here.

I feel their eyes again.

Their eyes are sharp teeth

that want to gnaw

and nibble me away.

MONDAY: READING AND WRITING CENTERS

I like to roll words in my mouth, like pebbles.

I like to read my books aloud.

I like the way stories unwind like Grandpa’s fishing line.

I like the way a good story puts pictures in my head

and little minnow-thoughts that dart and swim and wiggle.

I like to pretend I’m the hero with a magic sword,

or a Snow Queen, or a traveler from a faraway star.

I act out every part and every part is me.

My old teacher said, “Katharen, you were made for the stage.”

My new teacher says, “Katharen, why don’t you try again on the next page?”

YELLA? YELLOW?

“That’s not right.

That’s not how you say it,”

John Royale says.

“She said yella, Ms. Harner.

Tell her

“John,” Ms. Harner says,

“why don’t you read the next paragraph?

Thank you, Katharen, you read well.”

But the other kids giggle.

They giggle when I say yella.

They giggle when I talk.

“Katharen Walker,

you’re a funny talker,” they say.

“Why do you talk that way?”

RECESS

Girls on the monkey bars,

girls in circles,

girls in knots,

girls jump-jumping

under the basketball hoop,

girls that miss and skip and bounce and—oops!

Girls blowing bubblegum,

girls braiding hair,

girls chanting, “Dare! Dare!

Double-dare!”

Girl talk, girl telling,

girls whispering girl secrets.

Girl strut and girl sass—

but

—I’m by myself,

a fish flopping on a sandbar,

my thoughts turning in a circle,

my tongue tied in a knot.

STINGS

Chloe whispers, “This isn’t the South.”

Then she calls me ’Bama Mouth.

In math, no one wants to be my study buddy,

and Keith won’t share the book with me.

John Royale giggles. “Glad I’m not like you,

or I’d have that funny accent too.”

I pretend to erase their words away.

I pretend I can’t hear the things they say.

But sometimes, the mean is a bumblebee.

It buzzes and stings inside of me.

NOT YET

That clock is a snail.

Snail, I want to go home now.

Move fast, Snail. Move fast!

SCHOOL’S OUT!

I put my books away

I put my homework away.

I put my backpack on my back.

I put my hat on my head.

But where should I put

’Bama Mouth!

Katharen’s got a ’Bama mouth!

Where should I put

kids staring at me,

kids laughing at me,

kids saying, “You talk funny.”

Where should I put

the madsadbad

of being new?

When you’re not like them,

and they’re not like you.

Inside, question marks snag

Catching a Storyfish

Catching a Storyfish